Living with Kidney Disease: A Personal Journey

Living with Kidney Disease: A Personal Journey

The Life-Changing Phone Call

The phone call that alters one's life comes as a surprise. My call came on a Tuesday in March. I was in my car at the grocery store, awaiting my next errand when I scrolled on my phone. My nephrologist's measured, professional tone gave it away, yet I could still hear it—the careful gentleness—from her voice that made my chest tighten long before she even declared those words.

"Your creatinine is now 4.2. We should talk about dialysis."

I had been delaying this conversation months earlier. My kidney function had been on a slow decline, but somehow, I had convinced myself that if I just didn't eat protein, took my medications as if required, and showed up to each appointment with a smile and detailed food diary without having to mention declining health, I could do something to deceive the disease. My lab reports were all trending in the same direction upwards-creatinine plus, GFR minus, but they were just numbers on a page until that moment when they became a life sentence.

Life in the Dialysis Community

That was three years ago. Now, I'm writing you from my dialysis chair, number seven in a row out of twelve recliners, each chair becoming as familiar to me as my living room furniture. Next to me is a woman named Maria knitting what looks like the beginnings of a blanket for a baby. She comes here longer than anyone, almost eight years, and her fingers always move during treatment. Across from us is Jerome having an excited phone call with his grandson about a basketball game, speaking as loudly as he can, with excited joy from thinking about something other than the machine working quietly to clean his blood.

This is dialysis—ultimately coordinating your schedule, stress, and hope. This too, is an experience that is not found in a medical textbook—community should be not but a group of strangers who can become family, and the unexpected relationships that grow in the clinical uptakes, while in close physical proximity, with the same schedule, the same machines, and same hope for smooth days today and stable labs tomorrow.

The Early Signs: When Normal Wasn't Normal

But let me backtrack, knowing that my journey to this chair didn't start with that phone call. After all, it started years before this call, with what I believed to be the normal signs of getting older. The fatigue that crept in gradually, so slowly that I adjusted my expectations without really noticing. The way I'd find myself breathless after climbing stairs that used to be effortless. The persistent metallic taste in my mouth that I attributed to stress, to the new medications my cardiologist had prescribed, to anything except the possibility that my kidneys were quietly failing.

My primary care doctor caught it during a routine physical. A straightforward blood test, which is the same screening panel that had been performed for many years, indicated a shift in numbers this time. My creatinine had been stable at 1.2, for as far back as anyone could remember, had elevated to 1.8. Not enough to panic, but enough to refer me to nephrology.

Learning About Chronic Kidney Disease

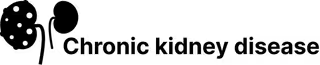

Dr. Sarah Chen became my nephrologist, and our first meeting was a true example of how to educate a patient. She didn't just explain chronic kidney disease; she drew pictures and told stories and somehow, even explained the gravity of my situation, without crushing my spirit. Dr. Chen stated my kidneys were like employees who have worked overtime for many years, and these were the first signs of burnout.

"What we can't do," she said, "is fix what's already done. We can only slow down the damage that is at the kidneys right now. Think of it like putting on a really good brake system on a car that is rolling down a hill. You cannot make the car go uphill, you can only control how fast it goes down."

The Early Treatment Phase

The beginning stages of the treatment certainly felt manageable, almost like a game, with specific rules about how to play. Take these pills at this time. Don't eat this food. Come in for labs every three months. Monitor your BP two times daily. I fixated on my lab results, tracking my declining kidney function in a spreadsheet that eventually grew into a massive database of my lab results. My family got used to measuring my disposition based on the results-a good lab result meant dinners to celebrate, a bad lab result meant quiet nights and worries and calls to Dr. Chen.

The Medication Journey

The medications came in trials. Our saga started with the ACE-inhibitor, lisinopril, which lead to a weekend-long cough my wife loathed while watching movies. Then, I took the ARB, losartan, which was better than the lisinopril, but took constant checks to ensure my blood pressure didn't get too low. Then, I started the SGLT2 inhibitor, dapagliflozen, one of those newer medicines that seemed almost too good to be true.

I will confess, I felt better than I had in months in the first few weeks on that medication. I had energy back, the constant low level of nausea that had become my new normal was gone, and I thought (hoped) maybe I had finally found the magic bullet.

But, as any patient with kidney disease knows, it is patient and persistent. Dapagliflozin bought me time-the good, quality time-but it didn't stop my GFR from continuing to decrease slowly. My GFR continued to drop slowly, hitting 45, then 38, then 32. Each of those sizes told the story of milestones degraded on a journey I never asked to partake in.

Navigating Dietary Restrictions

The Salt Restriction

I noticed I came to understand dietary restrictions as they came- the first gone was salt. Salt didn't seem like it was all that bad at first, however, I learned very quickly how much flavor I had taken for granted. Dinners out became an expedition of creatively articulating food, trying to remedy my appetite with requests like, "could you prepare the salmon with no seasoning, just lemon in its place?" or, "could I have steamed vegetables instead of roasted?" I had undoubtedly become that guy- the customer with ridiculous requests, hoping not to come across as the jerk.

The Potassium Challenge

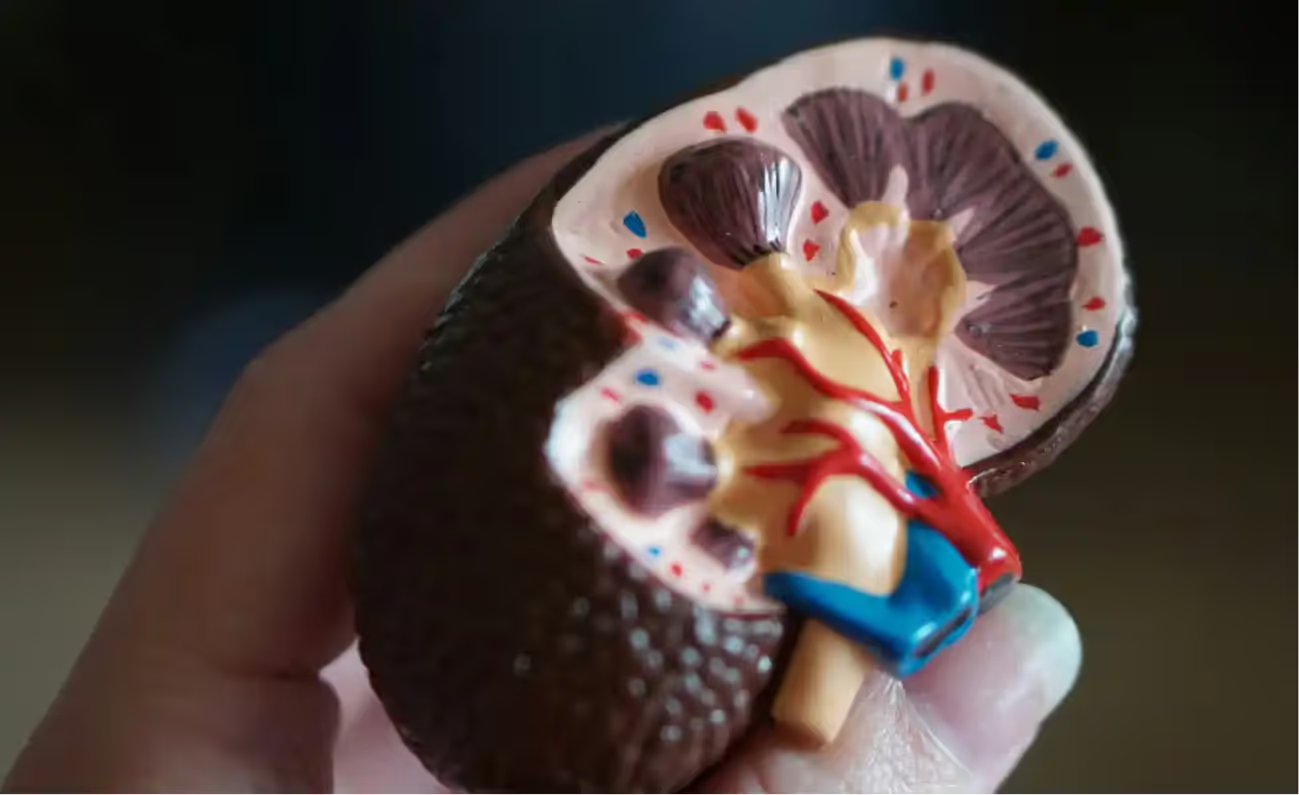

Potassium had a more steeper and tumultuous descent. Bananas had been a go to quick breakfast, I had perfected a banana & peanut butter sandwich for almost twenty years. Now, bananas were out, and considered forbidden fruit! Oranges, tomatoes, potatoes-these foods that I thought added to being healthy were now lethal foods for the chronic kidney disease patient. My wife and I would spend literally hours scanning every aisle of the grocery, calculating potassium content per serving as we read through beneficial labels. To make life even more challenging, we learned that food companies are not mandated to put potassium on nutrition labels, so meal planning became even more like a scavenger hunt.

The Hidden Phosphorus Problem

Phosphorus was the most difficult dietary restriction because phosphorous is hidden everywhere. Not just in dairy and nuts, but it found its way to almost every processed food, any soda, or anything that contained preservatives. I learned to fear the "phos" ingredients; sodium phosphate, calcium phosphate, phosphoric acid. Even bread became suspicious. We started baking our own bread using recipes we found on websites dedicated to renal diets that claimed "kidney-friendly" versions of many normal foods.

The Social Impact of Dietary Changes

I slowly learned to completely rethink my relationship with food. What once served as a social, celebratory time with family and friends had turned into a very elaborate mathematical calculation at meal times. Birthday parties were out of the question unless if I brought my own cake. Holiday dinners required extensive conversations with friends and family about the preparation methods and possible ingredients. I grieved for the simplicity of eating without thinking, the pleasure of ordering something new at a restaurant just because it sounded good.

Physical Complications

Bone Problems

The bone complications hit me hard, both physically and emotionally. The phosphorus that my kidneys could no longer filter properly began leaching calcium from my bones, leaving them brittle and weak. I broke my wrist in a fall that shouldn't have hurt me, and the X-rays showed bones that looked twenty years older than they should have. The endocrinologist gave me a prescription for an injection of synthetic parathyroid hormone once a week, which cost more each month than the car payment and needs refrigeration.

Sleep and Toxin Buildup

Sleep became a challenging endeavor as my kidney function worsened. The buildup of toxins that healthy kidneys would have processed left me feeling like an insomniac simply trying to survive. I would lie awake, hands itching from inside of my body in ways well beyond the scope of lotion, at 3 AM. My wife would find me in the living room, seated in my chair with a book or the TV on; anything to distract from the feeling of impending doom, like my body was assimilating into itself and slowly poisoning.

Anemia and Fatigue

The anemia was so gradual I didn't notice it until it was pronounced. What I thought at first was just normal age fatigue unbeknownst became serious when my hemoglobin fell below 9. Dr. Chen put me on synthetic erythropoietin injections and I learned to give myself an injection in the thigh twice a week. The first few times my hands shook so badly I couldn't even hold the syringe. Fast forward three years, I have jumped the learning curve and now administer the injections automatically, similar to brushing my teeth.

But even with the EPO the fatigue was overwhelming. Grocery shopping, lawn mowing, playing on the floor with my grandchildren, anything that once felt normal was now vertigo-inducing and exhausting in ways I had never felt before. I learned how to time activities around when I felt best during the day and usually I felt best first thing in the morning before the weight of the toxins became unbearable and some activities felt impossible.

Social Isolation and Relationship Changes

The social isolation was perhaps the hardest part of the pre-dialysis years. Friends stopped inviting us to restaurants because I'd become too complicated to accommodate. Family gatherings became stress-inducing events where well-meaning relatives would pepper me with questions about my diet, my medications, my prognosis. "Have you tried turmeric?" became a phrase that made me want to leave the room. Everyone had a story about someone they knew who'd reversed kidney disease with apple cider vinegar or some other miracle cure.

Work became increasingly difficult. I'm a high school English teacher, and standing in front of a classroom for six hours a day while feeling like I was moving through molasses required a level of acting skill I'd never known I possessed. My students were caught onto it, as they always do, but they were very kind about it—pushing chairs near me when they saw me moving a little during lectures, and even insisted on carrying large stacks of papers to my car.

Preparing for Advanced Treatment

The discussions I had with Dr. Chen changed after my GFR was 25. Our conversations changed from talking about slowing progression to talking about preparation. For the first time, the word "dialysis" appeared in my treatment plan, not necessarily immediately, but something we had to start thinking about more actively.

The Transplant Evaluation Process

She sent me to the transplant center for evaluation, and although it was a time of both hope and fear.The transplant team must have put me through every test they could think of—there was heart catheterization, pulmonary function, psychological assessment, dental clearance, etc. I remember the feeling of applying for a job that probably does not exist, and the interview lasted three months.

Psychological Assessment

The psychological aspect was taxing for me. The social worker was really thorough, asking lots of pointed questions relating to my support system, how I coped, if I could handle the stress of a major surgery and a lifetime of taking immune suppressive medications. She wanted to know that I was aware and prepared that a transplant was not a cure; I would be exchanging one set of medical difficulties for another. Did I have realistic expectations for life after? Could I get my mind around developing rejection and, even after a transplant, possibly going back to dialysis?

My wife joined me for this appointment, and I recall watching her answer questions of her own related to being a caregiver, only to learn how she went about understanding living with someone who was taking immune suppressive medications. The social worker told us that transplant recipients see higher rates of skin cancer, that even small leaks or other infections could have deadly outcomes, that we would think about everything differently, like gardening or traveling internationally.

The Waiting List Reality

Being accepted to be listed for transplant surgery felt like not only winning a lottery I never wanted to join, but also that the definition of waiting had only begun. The excitement of being accepted was close to muted, knowing that the best part was still ahead. The average wait time for a kidney in our region was four years. Four years of hoping that someone else's tragedy might become my salvation, four years of carrying a pager that would summon me to the hospital at a moment's notice, four years of maintaining my health well enough to be ready for surgery whenever that call might come.

Choosing a Dialysis Method

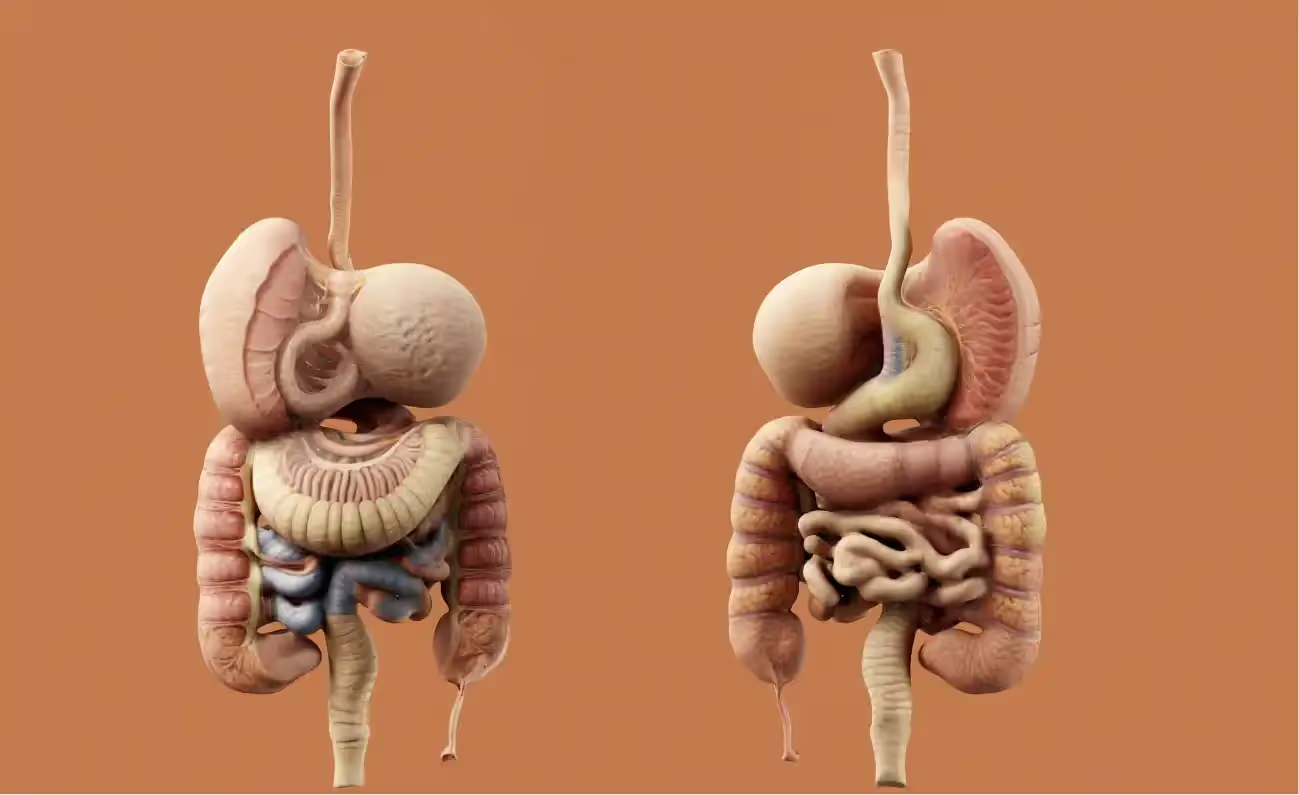

The decision about dialysis modality consumed months of my life. Dr. Chen arranged for me to visit both a hemodialysis center and to meet with patients who were doing peritoneal dialysis at home. Each option seemed to come with its own set of compromises, its own way of reorganizing life around the demands of staying alive.

Hemodialysis Center Experience

The hemodialysis center was both depressing and inspiring. The patients I met there had been coming three times a week for years, some for over a decade. They'd developed routines, relationships, ways of making the best of a difficult situation. The staff knew everyone's names, their families, their struggles and victories. But the time commitment was staggering—not just the four hours in the chair, but the travel time, the recovery time afterward, the way it chopped your week into rigid segments that couldn't be rearranged.

Considerations for Home Hemodialysis

Home hemodialysis sounded better in theory—more, shorter treatment that I could do whenever I wanted. But the training was intensive. I had to train my wife to be my partner in a medical process that was overwhelming. We spent weeks at the training center, learning how to run the machine, how to respond to alarms, how to respond to emergencies.The machine itself was the size of a small refrigerator, and installing it in our home meant converting our guest bedroom into a medical facility.

Choosing Peritoneal Dialysis

Peritoneal dialysis appealed to me because it seemed to offer the most normal life. Four exchanges a day, thirty minutes each, but I could do them at home, at work, even while traveling. The catheter surgery was relatively minor, and after it healed, I could maintain my teaching schedule, travel to see my children, maintain some sense of normalcy.

But PD came with its own anxieties. The risk of peritonitis—infection in the abdominal cavity—was constant. The sterile technique required for each exchange had to be perfect every time. One mistake, one moment of carelessness, and I could end up in the hospital with a life-threatening infection.

The supplies took over our dining room—boxes of dialysate solution stacked to the ceiling, boxes of tubing and masks and sterile supplies that made our home look like a medical warehouse.

I chose PD, partly because it seemed to offer the most freedom, but mostly because the alternative felt too much like giving up on the life I'd built. With PD, I could still teach, still travel, still feel like myself most of the time. The exchanges became routine—wake up at 5:30, drain overnight solution, instill fresh solution, head to work with a belly full of dextrose solution that would slowly pull toxins from my blood over the next few hours.

Living with Peritoneal Dialysis

Initial Adjustment Period

The first few months on PD were an adjustment period that tested my patience and my marriage. Learning to sleep with a catheter, finding comfortable positions that didn't kink the tubing, dealing with the body image issues that came with having a permanent tube protruding from my abdomen. My wife learned to give me space during exchanges while still being available if something went wrong. We developed a routine, a rhythm that worked for our family.

The First Peritonitis Episode

But PD wasn't without its complications. Six months in, I developed my first episode of peritonitis. What started as mild abdominal discomfort became excruciating pain, fever, and cloudy dialysate that looked like milk. The emergency room doctor took one look at my catheter and called the nephrology team. I spent a week in the hospital on IV antibiotics, feeling sicker than I'd ever felt in my life.

The infection cleared, but it left me shaken. The invincibility I'd felt mastering the PD technique was replaced by a constant low-level anxiety. Every slight change in how I felt, every variation in the appearance of my dialysate, sent me into a panic. Was this another infection brewing? Should I call the doctor? Was that abdominal twinge normal, or was my peritoneum inflamed again?

Dietary Challenges on Dialysis

The dietary restrictions on dialysis were different but not necessarily easier. With PD, I could be more liberal with fluids, which was a blessing after years of strict fluid restrictions. But the continuous glucose absorption from the dialysate solution made blood sugar control more challenging. I developed diabetes as a complication of my kidney disease and the dialysate, adding another layer of complexity to meal planning and medication management.

Social and Relationship Changes

After I began treatment through dialysis, I became more cognizant of the social dynamics related to having a chronic illness. Some friends rose to the occasion and either would reach out to me regularly or would adjust their social events to when I was comfortable getting together. Others, however, would fade either because they were unable to cope with the limitations of my illness or simply were uninterested.

Family Dynamics

Relationships with family members changed, too. My adult children became very protective of me, at times in a manner that felt suffocating. They checked in on my health multiple times per week, spent time researching treatment options for me online, and would send me articles related to experimental therapies.

Marriage Under Medical Stress

My relationship with my wife deepened in ways I hadn't expected. She became expert at reading the subtle signs of fluid overload, at recognizing when I was feeling well enough for social activities versus when I needed quiet time at home. She learned the names and dosages of all my medications, the signs and symptoms of peritonitis, the proper technique for catheter care. In some ways, she became as much a patient as I was, her life equally constrained by the demands of keeping me alive.

Continuing to Work

Work remained a source of normalcy and purpose, though it required constant accommodation. My principal was understanding about the need to do exchanges during the school day, providing me with a private space and flexible scheduling. My colleagues covered my classes when I had medical appointments or wasn't feeling well enough to teach. My students, perhaps because teenagers are naturally adaptable, barely seemed to notice the medical equipment I sometimes needed to bring to school or the days when my energy was obviously low.

Missed Moments

But there were moments of profound frustration. The day I had to miss my daughter's college graduation because I'd developed a fever and couldn't risk being in a crowd. The vacation we had to cancel because I'd developed a hernia at my catheter site. The constant background awareness that my life was now organized around medical schedules, that spontaneity had become a luxury I could no longer afford.

The Psychological Challenge of the Waiting List

The waiting list presented its own mental obstacle. Periodically, the transplant coordinator contacted me to inform me of my status and to remind me to keep my lab work up to date and my vaccinations current. She made a point of saying, "You are moving up," but the numbers were daunting. When I was first listed, I was number 847. Over the course of two years, I was number 312, which indicated some progress—but still a long time to go.

False Alarms

The false alarms were the worst. Three times in two years, I received a call that sent the adrenaline pumping: "We have a kidney for you. Come to the hospital immediately." Three times, I sped through the pre-operative process and thought I said my last goodbyes to my family. And three times, I was informed that the surgery was canceled because the organ was not suitable. A better match was found. The recipient had developed an infection that made surgery far too risky.

Each false alarm was devastating for its own reason. The first time, I felt like I had just been disappointed. The second time, I was angry and felt frustrated with a system that seemed to just play games with people's lives and emotions. The third time was worse: I fell into a depression that lasted several weeks. The psychology of preparing for a life-changing surgery only to have it snatched away was beginning to feel more stressful than the day-to-day experience of the dialysis process.

Finding Support and Community

The support groups helped, but I was hesitant to join them in the beginning. The notion of sitting in a circle to discuss kidney disease seemed depressing and indulgent, though Dr. Chen suggested I try it, and I met some people in the same position who understood things that my family, as lovely and supportive as they were, could not—namely, things like the grit of dialysis, the waiting for transplant calls, and the complicated implications of hoping for an organ to become available, while wishing that someone would die in order for that to happen.

Meeting Sarah and Tom

I met a woman named Sarah who was 34 and a mother of two, and we became friends. Sarah had been on the transplant waiting list for five years, having developed kidney disease from an autoimmune disease in her twenties. I appreciated her openness about the uncertainty and how she coped with it made me hopeful I could develop my own answers. "You can't live your life on hold" she said. "If the kidney is coming, it is coming. If it isn't, it isn't. Either way, your challenge is to find ways to be happy today."

Similarly, Tom was a retired firefighter who had been on hemodialysis for eight years. He talked to me about how important it was to be your own ally in the healthcare field. Tom had an ongoing log of every treatment he had experienced, could recite his lab values, and was not afraid to question the doctor if something did not feel right or line up with his previous medical experiences. He would say, "These doctors are good. But they are busy. You are the only one thinking about your health all day, every day." "Act like it."

Processing the Guilt

The group helped me process the guilt of having a chronic illness. The guilt of the burden I placed on my wife, the limits I placed on our social life, the concern I instilled in my kids, the guilt over the resources I was using—the dialysis treatments, medications, and hospital stays. The knot of guilt surrounding the transplant waitlist, knowing that by living, I depended on someones' worst days.

Present Day: Still Waiting, Still Living

I am still waiting. As it is today, I am number 127 on the transplant list, which is good, but may be months or years of waiting. My peritoneal dialysis is doing well—lab values are stable, the abdominal infection (peritonitis) has avoided me of over a year, and I am able to have a relatively active life with sometimes forgetting I am sick, and other days feel it is consuming me to manage my chronic illness.

Lessons Learned

I have learned about resilience, the human ability to acclimate to conditions that we never knew we would be stricken with. I have learned that one can continue to live overly while being medically dependent. I have found value in my experiences sharing them with new patients, including newly diagnosed patients, through the initial years of being the patient, providing them with a bit less fear and more insight over my own past experiences.

The Kidney Disease Community

The kidney disease community is large and diverse, both socio-economically, in geographic reach, ages throughout the lifespan, and ethnicities; however, we all share the connection beyond diagnosis—we commit to continuous living while finding purpose and positivity each day while navigating the world of non-functioning organs and medical craving therapies. We celebrate the small, shared victories—stable lab work, successful exchanges, and milestones of infection-free time.We help each other in the ups and downs of complications, hospitalization, and the natural progression of progressive disease.

Conclusion: Hope and Acceptance

My story is not unique in any way, but it is mine. Tomorrow I will do four more exchanges, take my medications on schedule and hope that the phone doesn't ring again from the transplant center to tell me it was another false alarm. Perhaps I will hope it does ring again, and it is the call that changes everything all over again.

Living with kidney disease has taught me that you can hold hope and acceptance at the same time; that it is not contradictory to plan for the future, while also being present in the current moment. The machine in the entry takes a soft beep and is finished with my treatment. Maria has finished her blanket for the baby and has started on what appears to be a matching hat. Jerome's grandson won his game yesterday, and Jerome is planning to attend the next basketball game.

In a few minutes, the nurses will disconnect me from the machine, check my weight and blood pressure, and schedule me for Thursday. This is the rhythm of dialysis life—routine medical procedures embedded in relationships, hope, and the determination to make the best of circumstances none of us would have chosen.